Counterintuitive Ideas on Making Money - Part 2: The 80/20 Principle

Why you can’t get ahead despite working your ass off

Originally posted to Actualizationhub.com on 3/15/21. Reposting here with a little editing (rewrote unclear sentences, removed unnecessary ones, and fixed some typo’s).

For an introduction on the purpose of this series, why you might consider caring what I have to say, and links to the rest of the series see Part 1: Introduction and My Story.

Part 2: - Pareto Distributions or Why Hard Work is a Trap

Introduction

If you put a gun to my head and forced me to choose only one thing to teach people about the world, it would be a difficult choice but I’d probably choose the Pareto Distribution (and its subsidiary Price’s law).

The super TLDR of Pareto is the 80/20 rule (fantastic book here). However, to distill it down this much does a disservice to its depth and far reaching implications. This video (13 min) is the best I know of that opens the door to its true utility both personal and societal.1

I am of course highly interested in the sociological implications of this concept but I will keep any comments related to “macro” stuff in the footnotes. The main article is geared specifically at helping you apply this concept to improve your skills, success, and wealth.

Let’s dive in.

Outlier Wealth Requires Outlier Strategies

The biggest mistake most people make about career and wealth is selecting strategies that satisfy at least one of three things:

Popular: choose them because they are easy to get in to or are in style.

adjacent: only a slight deviation from what they are already doing.

effective on average: eg tech fields on average are paid better than teaching fields, the index funds in your 401K perform better on average than any given stock, etc.

These strategies net mediocre results for most because:

Doing what most people are doing only works if you have the same skills that most people do. And actually because of how saturated this “popular” field is you will need to be significantly more skilled than them to get ahead.

Doing what’s adjacent to your current life only works if your current life is mostly working for you and just needs a little tweak. For those of us born outside of the upper class, this is obviously not going to get us there.

Doing what is effective on average only works if your goal is to achieve average results. Average results aren’t terrible. But they certainly aren’t optimal. From my experience they look something like: working your tush off to fulfill all your have-to-do’s, with little to no room for your want-to-do’s thus neglecting your health, relationships, and potential all so you can just barely scrape by financially.

If you want outlier results, you must use the strategies outliers use.

But if you read this blog you likely already know and do this. You probably fill your library, Youtube, podcasts, and bookshelf with hours and hours of advice from hyper successful people. And still, to your interminable frustration, you end up with unsatisfactory results. Why?

As I discuss in this article, this is largely due to world class performers failing to actually isolate the relevant (to us) components of what made them successful. They can tell you all about how they got from the top 10% to the top 1%—or even the top 0.1%—But they don’t actually have jack to say about how they got from the median to the top 10%. Why? Because for them that part was not a strategic, conscious endeavor. Just dumb blind luck. The stars happened to align in a way that their innate talent coincided with a great opportunity and their life situation allowed them to capitalize on it. Not exactly reproducible.

And thus all the stuff you see in every book, interview, biography, or whatever else from these world class performers about how you just need to work harder, have more discipline, and believe in yourself more will not help you.

Yes, they are exceptionally disciplined, hard working, and confident compared to the vast majority of people. And you need to get good at these things too. But these things will only take you from the top 10% to the top 1%. They will never help you much if at all in getting from the top 50% to the top 10% (what all the rest of us are trying to achieve).

So if even doing exactly what all the successful people advise you to do still sucks, what’s left?

Well just because the self perceived causes of outlier results obfuscates the actual causes doesn’t mean that social scientists, psychologists, and economists who have been analyzing this problem from a statistical perspective for over a century can’t identify them. And thankfully for us they largely have. And one in particular has done, in my opinion, more than any other on this front.

Enter: Vilfredo Pareto.2

Skills Are Distributed Linearly, Results Are Distributed Exponentially

From the work of Pareto—and the subsequent propagation and simplification of his ideas—we have learned pretty conclusively that the first and most important truth to outlier results is:

The top 20% of players in any given domain accrue 80% of the rewards in that domain.

The top 20% of programmers make 80% of the money.

The top 20% of comedians get 80% of the gigs.

The top 20% of communicators have 80% of the influence.

The top 20% of YouTubers get 80% of the views.

The top 20% of books get 80% of the reads.

And so on.

And because the remaining 80% of players have to fight over the scraps (the remaining 20% of rewards), seeking to achieve slightly-above-average is a massive waste of time and energy.3

This distribution forms for a few key reasons and knowing them is critical to leveraging the Pareto Principle maximally.

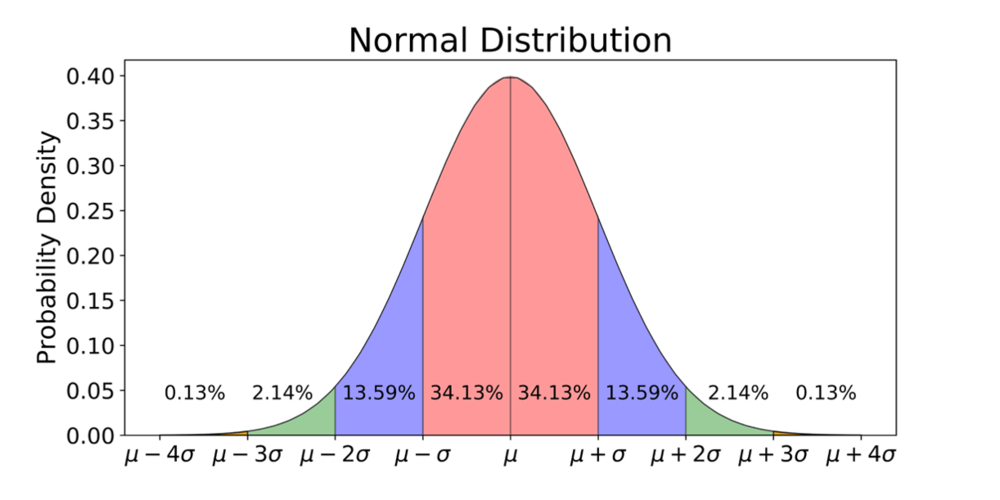

1. Skills Are Distributed Along A Normal Distribution

Most things, abilities included, are distributed along a normal distribution. The famous bell curve anyone familiar with statistics has seen before.

If you’re new to this concept, let’s use people’s computer literacy to demonstrate.

Most people’s computer skills clump around “decent”. They make up ~70% of people (salmon colored area) and are proficient at sending emails, browsing the internet, changing basic settings, downloading and installing apps, etc.

To their right are a small group of people (purple, 13%) particularly good with computers. They are able to do more complex things like use VPNs, torrents, make changes to their router, sometimes use the command line, etc.

And to their right are an even smaller group (green, 2%) of people who are really good. These people usually do IT professionally, able to set up servers, write scripts, use the command line daily, etc.

And to their right are a tiny group (orange, 0.13%) who are exceptionally good. These people are those at the top of this field, able the set up, run, and troubleshoot massive enterprise infrastructure, etc.

And then we basically have a similar distribution but in reverse on the other side. A small group (purple, 13%) that struggles to do basic things like email, browsing, downloading; an even smaller group (green, 2%) who basically don’t use computers at all; and then an even smaller group (orange, 0.13%) who have never used a computer.

This same kind of distribution applies to any skill or knowledge set whether it be toward computers, cooking, football, dancing, writing, speaking, or whatever else.

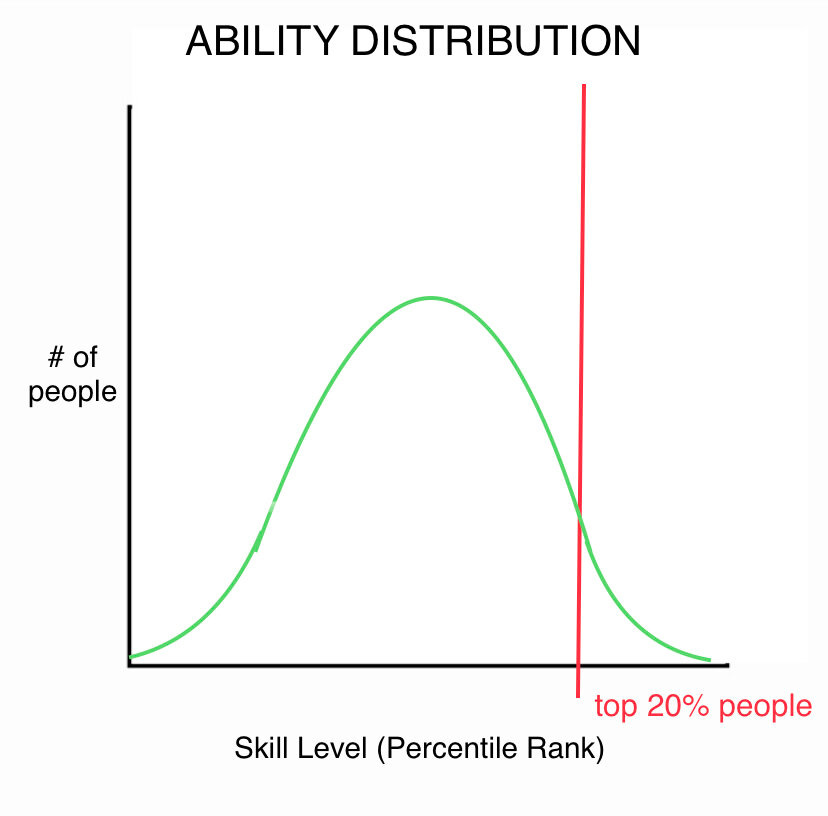

2. Skill Development Follows the Law of Diminishing Returns

Skills are distributed this way largely because skill development follows the Law of Diminishing Returns.

This means that the amount of effort, energy, and time necessary to develop one unit of skill rises exponentially as you get better at it. But because exponential increases in time and effort is still minimal when numbers are small, most people can become proficient at basic skills quickly (ex two minutes doubled twelve times is still only a single workday).

However, once you reach a certain point the amount of time and effort necessary to increase your skill level goes up astronomically (ex the twelve more doublings it would take to make as much progress as you did on the first day would require thirty years).

If this sounds confusing, consider any sport or board game or video game.

In an hour you can get the basics down enough to play it (the first ~50%). To become proficient at it may take several hours (the next ~25%). To become an expert at it will take dozens if not hundreds of hours (the next ~20%). And experts will spend the rest of their lives trying to master it (the last ~5%).

The first 50% is completed in minutes. The last 50% is not completed for decades (technically never).

Even a less complex scenario like taking a test follows the same trajectory.

If you knew nothing about the subject, you could probably pass a test on it after an hour of study (first 60%). To get a B (+20%) would require you to double your study time. To get an A (+10%) would require another doubling. And to get 100% will take another doubling at least.

One hour for a passing grade. Eight or more hours for a perfect grade.

Most things are this way—“great” takes ten times longer than “good” which takes ten times longer than “bad”. And its why skills form normal distributions.

3A. Skills Compound on Each Other

Next you have the fact that the world is complicated. Success within it requires not just one skill but many complementary ones working together.

As a result, being proficient at multiple skills is “greater than the sum of its parts”, having a multiplicative rather than additive effect.

This is where the magic of things like talent stacks come in (or, inversely, where the curse of being too hyper specialized comes in).

These compounding effects are why the IT guy with average technical skill but decent social skills can rise up through the ranks, but the IT guy with exceptional computer skills and horrible social skills keeps getting fired. (Minus the tiny portion of them who got lucky and bypassed the first hurdles to end up running the whole industry).

Or why being only slightly above average at cooking or speaking or video editing or photography or attractiveness might get you a job but being all of them can make you millions doing a YouTube cooking channel.

3B. Results Compound on Each Other

Skills don’t just compound. Results compound too.

This is often called the Matthew Principle—the rich get richer the poor get poorer.

If you don’t have any money at all you can’t pay your bills, or get a bank account, or build credit, or pay for education, or even get off the starting line.

However, if you can get one of them it makes you more likely to get the next. And having five of them makes the sixth almost guaranteed.

Similarly, when you move somewhere new and have no friends getting one is hard. But once you have one they can introduce you to five more and each of them five more. Zero to one is just as hard as one to fifty.

Or how if you’ve never had a job getting your first is hard. But getting a promotion within it is less hard. And using it on your resume to get your next job is even less hard. And once you have “Sr Engineer at Microsoft”, you can basically get a job anywhere for any amount of money.

I could go on but I think you get the point: the more you have, the more you can get.4

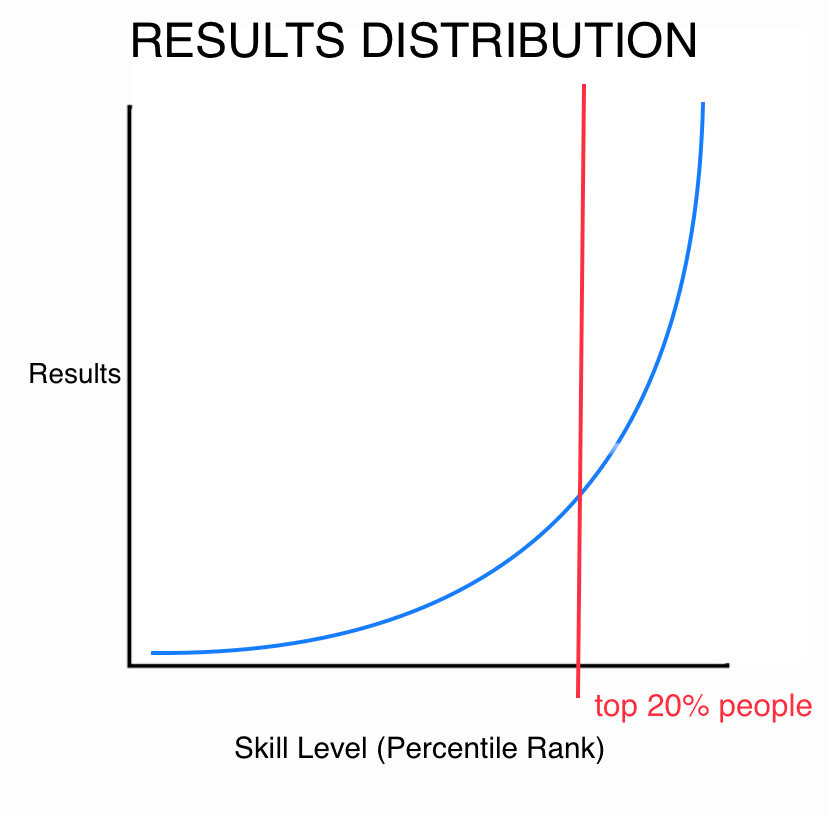

4. Results Are Distributed Along a Pareto Distribution

Because of these four things (and probably one or two more I am forgetting or don’t know) results are organized along a Pareto Distribution—where all the rewards accrue to those at the top.

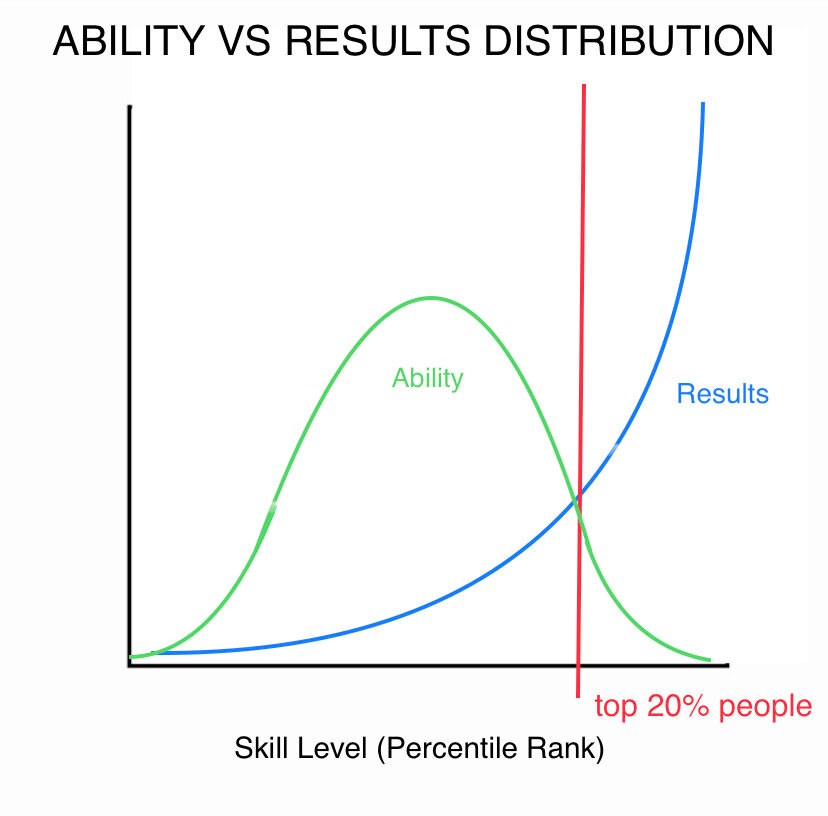

If you take nothing else away from this article, I want you to take the following image and sear it into your brain.

Now do you see why trying to achieve slightly above average results is a total waste of time? It’s the worst of both worlds. You have to work your butt off and you hardly get anything more than those that barely work at all.

This is why the top 20% make 80% of the money.

The vast majority of people I know who make over six figures work less than twenty hours a week. In fact the richest person I know, who makes seven figures a year, works less than ten. And she wasnt born rich. Her family are lower middle class immigrants. She has just been optimizing via Pareto every day for over a decade.

Further, this is why the top 1% make 50% of the money.

On any given skill or trait: Brad Pitt is only a little bit better than Joel Kinnaman. A little more handsome, a little more charismatic, a little more skilled, a little harder working. All likely in the fractions of percent’s compared to the entire distribution of actors. But he is paid $10M to be in a movie while Joel is paid less than $1M. Why? Because Pareto.

This same distribution applies to everything from scientific papers published, books sold, songs played, videos watched, rights swiped (dating apps), restaurants frequented, cities moved to, and news outlets read.5

Inequity is the natural state of reality. And If you want to tip it in your favor you must first understand that this is the case and why it is the case.

Conclusion

To sum this all up:

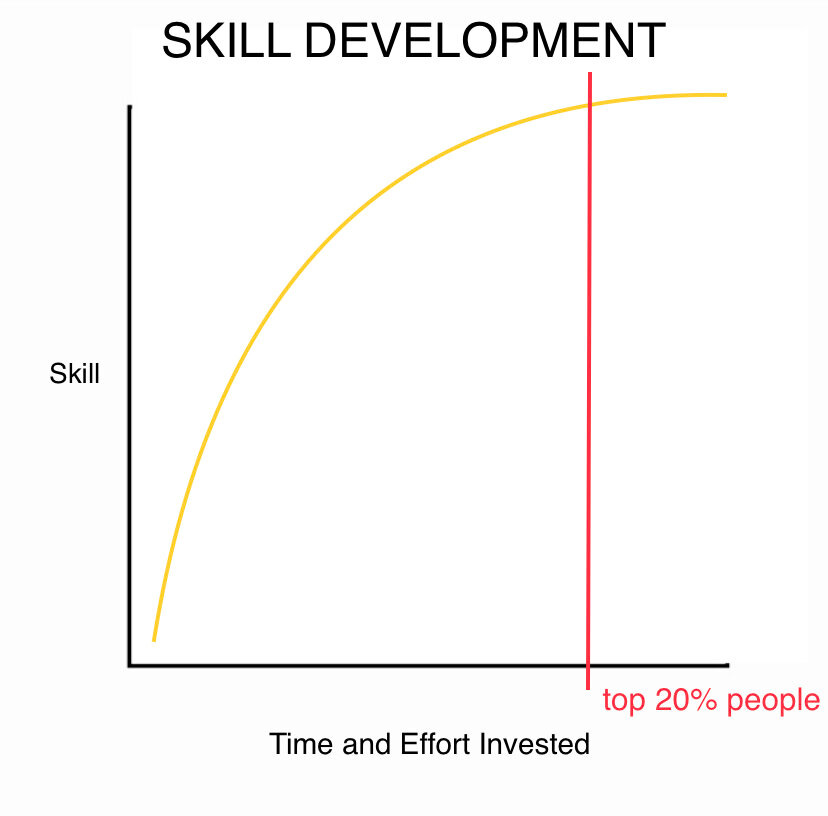

1. It’s relatively easy to achieve proficiency in most things.

2. It’s exceptionally hard to get beyond proficiency. But those who do end up accruing all of the influence and money in that field.

3. Only those who maximally leverage their innate talents and interests—and thus can enter the top 20% of a domain with little to no effort—can ever break into the upper bounds of this curve.

4. Thus, if you want outlier results, hard work is a red herring. It is at best an exponent applied to a base of talent, passion, joy, and skill and at worst completely unnecessary.

In part 3 of this series, I’ll go into depth on some of the best ways to apply this new understanding from my own experience as well as reading widely about what has worked for others.

If you want to be notified as soon as part 3 is released, be sure to..

Here’s that whole lecture the 13 min clip is from if you want more on it.

I can’t help but think of this scene when saying his name.

This truth is why your status within the middle class is basically directly correlated with how many hours a week you work but there is almost no correlation for the lower class (you get generally poor results regardless of how much you work) nor the upper class (you get generally good results regardless of how little you work).

Further, it is also largely why “conservatives” who make up most of the middle class believe that “picking yourself up by your bootstraps” is the solution to all problems. Because that literally is the best strategy if your goal is to move up within the middle class. And why “liberals” who are mostly upper and lower class think this is dumb. Because in both of their experiences, hard work or it’s lack doesn’t move things much in either direction.

This fact specifically is why the upper class don’t have to work much to succeed and the lower class don’t see much success regardless of how much they work. Because the compounding effects through time, space, and social network make everything come easy to the former and excruciatingly difficult for the latter.

And further, this is why humans as a whole have built more in the last few hundred years than we did in the proceeding hundred thousand.

And Pareto doesn’t just apply to humans. Or even living things. The accretion of mass in the universe forms a Pareto Distribution—completely by chance I might add.

The reason we have planets and stars and galaxies is because when a random (aka normal) distribution of different sized tiny clumps of mass are created:

Clumps that, through total luck, started slightly bigger attract more smaller clumps to them than the smaller clumps would to themselves (because they have more gravity). And then as the clumps get even bigger they can attract even more small clumps. And this repeats and repeats until a few big clumps functionally suck in everything suck-in-able and then a few Schelling Points of equilibrium later and now you have asteroids orbiting moons orbiting planets orbiting stars that make up solar systems orbiting black holes that make up galaxies that make up galaxy clusters that make up galaxy super clusters that make up galaxy filaments that make up the whole universe!!!

This is interesting. Because one thing is to be an outlier and in the top 1% or 0.1% in skills, let's say programming, and another one is to achieve outlier status economically, sometimes they are disconnected. It comes to mind the idea that Corporate Machiavelli expressed in one of his tweets, that the difference between the middle and upper class is IQ, but the difference between the upper class and the rich is that the latter is more cunning and risk aggressive. Just think about those who bought crypto early on, the truth is that they didn't have a special skill, they just were more risk aggressive. Another example is the guys working several remote programming junior jobs, around 4-5 at the same time, they have average or above-average coding skills but they are making 700k+ a year only because they took the risk and are more cunning than the average programmer. This means that if you're not capable of getting to the top by raw skills alone you can still get there by optimizing those 2 factors in any way possible inside your professional domain or even outside of it. What do you think?